Kunisada Exhibition

Utagawa Kunisada’s 69 Stations of the Kisokaido, 1852, a special exhibit for the Dean’s Gallery of the College of Arts & Architecture, May-June 2015, BOZetto, Vol. 3, Spring 2015, 5-11.

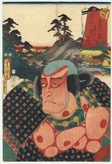

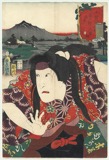

In the first half of Spring Semester 2015, Professor Todd Larkin taught a truncated seminar of nine undergraduate and graduate students on the topic From Royal Treasury to Public Institution: The Origins of the Modern Art Museum, ca. 1630-1830. The capstone project for this course was an exhibition of twenty-four individually framed woodblock prints from Utagawa Kunisada’s less well-known portrait series 69 Stations of the Kisokaido (1852). The series, which pretends to represent the most prominent kabuki actors of the period enacting their most famous roles at various points along the inland forested highway, was thoroughly explained in relation to printmaking techniques and kabuki theatrical practices as follows.

Katrin Cottingham, “The Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kisokaido Road”

The Kisokaido (also known as the Nakasendo Central Mountain Road) was one of five centrally administered network road systems in Japan called the Gokaido. During the Edo Period (1603-1868) many political, social, and legal changes occurred, including the repair of Japan’s thousand-year-old road system. The administration approved the rejuvenation of five major routes: Nakasendo, Tokaido, Koshukaido, Oshukaido, and Nikkokaido. The Kisokaido was an inland scenic route connecting the political and administrative city of Edo (present day Tokyo) with the imperial residence located in Kyoto. Along this scenic route were small towns with dedicated post stations established for use by feudal lords (daimyo), the military (shoguns), and official couriers. These post stations had their own unique appeal and could be associated with a famous site, a popular view, a historical reference or perhaps a local specialty (meibutsu, a term associated with famous products produced by specific regions). Because the Kisokaido was so well developed it acquired popularity with famous authors, poets, and artists who portrayed the Sixty-Nine Stations through their various disciplines.

Andrew Buck, “Kunisada’s Riddles: Kabuki Actors and the Kisokaido Road”

In this series of prints, Kunisada juxtaposes kabuki actors, who hail primarily from the urban sphere, and the way stations along one of the most rugged of Japan’s highways, the Kisokaido. The actors are separated spatially and conceptually from the landscape by a stylized band of clouds. Kunisada’s choices reflect a desire to present each print as a riddle that highlights the relationships that exist between the world of kabuki performance and the sixty-nine stations along the highway.

Highly reproducible and easily distributed, actor prints promoted the popularity of kabuki performance. Although the Japanese public collected them with the same passion Americans enjoyed baseball cards or Hollywood glossies, Edo officials regarded actor prints with great suspicion, often issuing censorship edicts. It is likely that the character or performance shown in the print was not being performed at the time. Audiences of kabuki simply wanted to be reminded of certain favorite characters or scenes from plays as opposed to the entire biography or performance. Kunisada shows historical and contemporary actors in the midst of performing these well-known scenes and roles.

Kunisada was a great innovator in woodblock printing because he was able to combine the actor’s portrait with a landscape. The Kisokaido was a route sanctioned by the Edo government around 1716. It was a rugged mountain trail that was much more difficult to traverse than the coastal highway to the south, but it allowed the traveler with official business to avoid the crowds that accumulated along the preferred route. Kunisada intended the landscape depicted in the prints to signify the stations which served as rest-stops along the route. As points along an important and historical highway, these stops became integral to the folklore and cultural history of Japan.

Finally, actor-landscape pairings are meant to be read as riddles. The riddle can occur in four ways: a play connection, legendary or literary connection, homophonic connection, and pun. Play connections referenced points along the Kisokaido that featured prominently in a specific play. Legendary connections referenced the lore that had grown up around the road itself, perhaps showing a warrior at the location of a famous battle. Homophones, plays on words, relied on connections between character names and place names, such as warrior Kumagai Naozane’s placement at Kumagaya (Station no. 9). Puns were conceived by relating place names to events referenced by the play, character, or local stories.

By pairing kabuki characters with identifiable locations, Kunisada established a standard iconographic formula. His combination of human and geographical subjects was carefully formulated to create a riddle for the kabuki aficionado. Although the actor subjects are not linked to the landscape through formal composition, they are connected through specific intellectual and cultural references. Kunisada effectively associates urban kabuki theater culture with the travel routes and folklore of Japan.

Andrew Buck, Katrin Cottingham, Emily Danielson, Stormy Du Bois, Chelsea Higgins, Meghan Livers, Jackie Meade, Jesine Munson, and Amanda Williams, “Object labels with interpretive essays”

The twenty-four prints selected for display are meant to reflect the variety of actors in vogue and an equitable distribution of stops along the Kisokaido. All of the prints are composed of polychrome ink on mulberry paper, roughly 14 by 9.5 inches. Here is a sample of six:

Amanda Williams and Andrew Buck, “Censorship and Printmaking in Japan”

Censorship of prints in Japan has a long history, with waves of strict enforcement stretching back to the 1720s. Scholars can gain information about print censorship through multiple avenues, including the edicts issued to artists, publishers, and buyers and anecdotal accounts of the punishments that were visited on those thought to have broken the edicts. All prints were required to carry the name of the author and publisher, together with a special censor seal that showed that they had official approval to print.

Elements most frequently banned from appearing in prints included the following: unorthodox religious views, commentaries on current events, overly luxurious treatments, information contained in calendars and almanacs, mention of high ranking families, and morally questionable content such as erotica. These bans were always met with resistance on the part of artists and buyers. Prints of actors proved especially troublesome to the censors and were regularly banned. However, these likenesses could be difficult to police since they were so recognizable as faces that it mattered little if their names actually appeared on the print.

Even though the government censors were strong during the Edo Period, they served as a creative driving force in the world of printmaking. For example, they forced artists to adapt and to shape their styles in ways that lead to unique formal solutions and sophisticated political-social messaging.

Chelsea Higgins, “Kabuki Theater Portrayed in Print Triptychs of the Edo Period”

Kabuki is a classic and unique form of Japanese theater that reached its zenith in the Edo Period (1608-1868). While kabuki was mainly active in the city of Edo, it also thrived in the urban settings of Kyoto and Osaka. Beginning as a form of entertainment for all social classes, Japan’s lowest classes largely appropriated it after 1713 following a series of court scandals. Kabuki became a popular subject for Japanese woodblock artists. Printed editions reveal the artists’ interest in representing kabuki in a variety of ways, whether incorporating various components of theater production, whether acknowledging the publicity machine or indicating actor preparation, performance, and audience reception.

Publicity for Performances: Japanese woodblock print artist Kunisada provides a sense of the advertising involved in promoting kabuki productions. In this print entitled Kabuki Signboards (1858), Kunisada depicts figures passing through a busy street in Edo, while billboards announcing different kabuki shows and popular actors line the street behind them.

Preparation Behind the Scenes: Print artist Kuniyoshi gives a “behind the scenes” view of actors preparing for a kabuki production. Backstage at a Kabuki Theater (ca. 1830-1846) reveals the bustling activity that took place behind stage before and during a performance. Characters are seen in the midst of various stage preparations, including assemblage of costumes, application of makeup, and styling of hair and wigs.

Performance: Kunichika’s Catching a Young Warrior Off Guard (1865) renders a scene from a famous kabuki play entitled Ehon Taikoki, depicting five actors—a samurai, his son, and their female relations. Each actor enlivens his role in the performance through his animated expression and unique and elaborate costume. This print provides an indication of the exaggerated visual impact of a kabuki performance upon the audience.

Audience Participation: Toyokuni’s Interior of the Nakamura Theater, Edo (ca. 1800) is a representation of a kabuki theater as it may have looked in the Edo period. Performers are able to enter and exit via an elevated platform (hanamichi), thus stirring audience enthusiasm. The active audience is seen facing different directions, eating and drinking, and yelling out. Audience engagement with the performance is essential to kabuki as a complete art form unique to Japan.

Jackie Meade, “Introduction to a filmed performance of Tsuuchi Jihei and Tsuuchi Han’emon’s play, Sukeroku (1713)”

Sukeroku is among the most popular and famous of kabuki plays. The story centers on the character Sukeroku, who is a samurai and an otokodate (or reckless hero from the samurai class, poor yet uninterested in reward). The play is well known for a number of iconic elements, including Sukeroku’s purple headband, bullseye pattern umbrella, and distinctive face makeup pattern. Sukeroku is a prominent patron of the Yoshiwara and especially of the Agemaki, the top courtesan of the Miura-ya teahouse. He moves with stylized and exaggerated paces and gestures meant to evoke general manliness and specific reactions to the situations with which he is confronted. Sukeroku is later revealed to be Soga Goro in disguise who seeks out his father’s killer and avenges his father’s death. His utterances become ferocious and his movements determined.

Katrin Cottingham and Todd Larkin, “Costumes and accoutrements: Kimono and Uchikake, Katana and Tanto, Sensu and Kiseru”

The men’s kimono (literally “thing to wear”) is simpler than the women’s garment, consisting of shorter sleeves and varied hem lengths. The most formal style is plain black silk with five kamon (crests)—on the chest, shoulders and back—and is often decorated with an intricate pattern. In this example, the freestyle pattern largely adheres to the lower half of the garment and consists of a gentle stream which nourishes a variety of flora and fauna, including peonies in full bloom, cranes in flight, and other decorative motifs. The redolent imagery and muted palette indicate that this kimono is meant to be worn in early summer. Although the most popular process for making a kimono is to tie dye the material, the intricate patterns seen here were created by a hand printing process and partially embroidered.

The uchikake (wedding coat) is a highly formal coat worn only by a bride at a stage performance. In this example a kosode design (narrow sleeve opening) is illustrated, emphasizing long flowing sleeves which became popular during the Edo Period. Meant to trail along the floor, this wedding coat is heavily brocaded with a padded hem and incorporates red silk with couched gold thread embroidery and a figured ground pattern. The ground pattern design consists of delicately placed images of plover birds, cloud patterns executed in a tatewaku (undulating line), and scattered diamond lozenges. The embroidered pattern is of flowers and bamboo fencing with flying cranes and moko (melon) crests which are located along the upper shoulder sections.

Bushi or samurai were part of a professional class of warriors that emerged in the late twelfth century who waited in attendance on the emperor and the nobility. Although they were originally charged with putting down rebellions in the provinces for the emperor, they gained a measure of wealth and status in the service of rival shogun clans—the Fujiwara, Taira, and Minamoto—and came to dominate the government and to find acceptance at court. By the seventeenth century, samurai families were compelled by the stable and peaceable Tokugawa shogunate to indulge in aristocratic pastimes like calligraphy, poetry and music; to moderate their identity towards the cultivation of bushido (“the way of the warrior,” a code of moral conduct meant to serve as an example of behavior for others); or to become scholars useful to administration and record keeping. Their exploits in battle were now the stuff of legend rather than experience, and they clung to their old weaponry as signs of status as “warrior nobility.”

Most of the types of metal weaponry employed by a samurai had assumed characteristic forms and purposes by the late eleventh century, although improvements in the heating, folding, hammering, and sharpening of steel continued in subsequent centuries, resulting in blades of tremendous strength and fatal sharpness. In the case of combat from a distance, a samurai relied principally on his bow and arrows to subdue a foe. In the case of hand-to-hand combat, he preferred to brandish a lance, although he also carried two “samurai swords”—the katana (or long sword) and the wakizashi (short sword), whose blades had a slight curvature, sharpest on the convex edge, which were kept in scabbards slung (blades upward) from special sword belts on the left side. He also carried a tanto (or dagger) that had an almost straight blade, which dangled from a sash at the waist. The long sword was used with great downward force to strike and sever the armor (often the helmet) of an opponent; the short sword was used with lateral pressure to behead an enemy; and the dagger was used in rare instances to stab an opponent or to commit seppuku (ritual suicide). Wearing and using the katana and wakizashi was a privilege reserved for samurai.

The earliest sensu (folding hand fans) were made of thin slats of Japanese cypress that were stacked and bound. During the Edo or Tokugawa Period (1603-1868), fans were made by pasting paper—hand-colored, calligraphy-inscribed, or brocade-lined—to a skeleton of split bamboo. Just about every social class used them, from the emperor, shogun, and regional lords to samurai, merchants, and actors. A fan could be employed in several ways—pragmatically, as a means to cool oneself in the summer heat, rhetorically, as a means to express oneself or to direct attention to another, or modestly, as a means to hide one’s laughter or expression. Merchants would even use their fans as a kind of appointment book or ledger, inscribing important meetings and contacts directly on the paper!

Smoking tobacco had long been a custom in the Americas before Columbus sent scouts into the West Indies/Cuba in 1492. The Spanish and Portuguese spread the custom to Europe, and the cultivation of tobacco in Central America became a major part of the colonial system, involving American Indian and African slave labor. Portuguese traders introduced tobacco to the Japanese in 1542 and it remained a regular pastime for the wealthy or a custom employed on special occasions by the middle class. Daimyo, samurai, and chonin smoked tobacco and carried a kiseru (pipe) in a kiseruzutsu (case), which was connected to a tobako-ire (small tobacco pouch). The Japanese pipe had a smaller bowl than the typical Dutch all-clay pipe familiar to Europeans, the middle section consisting of hollow bamboo and the ends made of iron, bronze, or silver, which could be decorated with intricate designs befitting a status symbol.